Dillon Read & Co. Inc. & The Aristocracy of Stock Profits (Part 2: Chapters IX-XIII)

By Catherine Austin Fitts

This post contains chapters IX - XIII. Please find Part 1: Chapters I-VIII here.

Total Chapters: XVIII. Originally published 2005.

IX. Cornell Corrections

Based on company SEC filings, Houston-based Cornell Corrections started off with correctional facilities in Massachusetts and Rhode Island in 1991 and then in 1994 acquired Eclectic Communications, the operator of 11 pre-release facilities in California with an aggregate design capacity of 979 beds. An important relationship for Cornell from the start was the U.S. Marshals Service, an agency of DOJ, who was Cornell’s primary client for its Donald W. Wyatt Federal Detention Facility in Central Falls, Rhode Island, a facility with a capacity of 302 beds.

The U.S. Marshals Service is the oldest U.S. enforcement agency. Among other duties, the U.S. Marshals Service houses and transports prisoners prior to sentencing and provides protection for the federal court system. According to the Marshals Service’s website, they are also:

“Responsible for managing and disposing seized and forfeited properties acquired by criminals through illegal activities. Under the auspices of the Department of Justice Asset Forfeiture Program, the Marshals Service currently manages more than $964 million worth of property, and it promptly disposes of assets seized by all DOJ agencies. The goal of the program is to maximize the net return from seized property and then to use the property and proceeds for law enforcement purposes.”

An article by Jeff Gerth and Stephen Labaton in the New York Times in November 1995, ‘Prisons for Profit: A Special Report; Jail Business Shows Its Weaknesses” describes the problems that Cornell ran into with its Rhode Island facility. This facility had been financed with municipal bonds issued through the Rhode Island Port Authority in the summer of 1992 and underwritten by Dillon Read. The article states:

“Two years ago, the owners of the red cinder-block prison in this poor mill town threw a lavish party to celebrate the prison’s opening and show off its computer monitoring system, its modern cells holding 300 beds and a newly hired cadre of guards.”

But one important element was in short supply: Federal prisoners.

“It was more than an embarrassing detail. The new prison, the Donald W. Wyatt Detention Facility, is run by a private company and financed by investors. The Federal Government had agreed to pay the prison $83 a day for each prisoner it housed. Without a full complement of inmates, it could not hope to survive.

“So the prison’s financial backers began a sweeping lobbying effort to divert inmates from other institutions. Rhode Island’s political leaders pressed Vice President Al Gore while he was visiting the state as well as top officials at the Justice Department to send more prisoners. Facing angry bondholders and insolvency, the company, Cornell Corrections, also turned to a lawyer who was then brokering prisoners for privately run institutions in search of inmates.

“The lawyer, Richard Crane, has done legal work for private corrections companies and Government penal agencies. He put the Wyatt managers in touch with North Carolina officials. Soon afterward, 232 prisoners were moved to Rhode Island from North Carolina, and Mr. Crane was paid an undisclosed sum by Cornell Corrections.”

Cornell’s Donald C. Wyatt facility later became a case study at the Harvard Design School’s Center for Design Informatics. This was an indication of the wave of business and investment opportunities that prisons and enforcement presented to everyone from architects to construction companies to real estate and tax-exempt bond investors.[42] Harvard’s case study mentions that Cornell arranged for the facility to be constructed by Brown & Root of Houston, Texas, then a subsidiary of Halliburton. (Brown & Root, now known as KBR, separated from Halliburton in April 2007 after 44 years as a subsidiary.) Brown & Root/KBR’s construction of prison facilities was to become more visible many years later after its construction of detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay, prisoner of war camps in Iraq and its winning of contracts to build detention centers for the Department of Homeland Security. A request to Cornell for information regarding companies used for prison construction subsequent to the Wyatt facility has been made, but no response has yet been received.

Dillon Read had long standing relationships with Brown & Root and the Houston banking and business leadership as a result of the firm’s historical role in underwriting oil and gas companies, including pipelines. In 1947, Herman and George Brown, the founders and owners of Brown & Root, were part of a group of Texas businessmen banked by Dillon Read as investor and underwriter (in a manner very similar to Dillon’s backing of Houston-based Cornell many years later) to form the Texas Eastern Transmission Co. to buy the “Big Inch” and “Little Big Inch” pipelines in a privatization by the U.S. government.

The Texas Eastern pipelines were critical to bringing natural gas from Texas and the Southwest to Eastern markets. For most Americans, Houston and New York seem far apart. However, the intimacy of their connection is better understood when you study the investment syndicates that controlled the railroad, canals, pipelines and other transportation systems that have connected these markets and helped to determine control of the local retail businesses for both goods and capital along the way. For example, Texas Eastern’s Big Inch pipeline went from east Texas to Linden, New Jersey, some 30 miles away from the Dillon and Brady estates in New Jersey and approximately 20 miles from the Dillon Read offices on Wall Street.

According to investigative journalist Dan Briody in The Halliburton Agenda: The Politics of Oil and Money, the Brown brothers netted $2.7 million in profits on their shares in their initial public offering right after the company was formed and won the bid to buy the pipelines from the government in the late 1940’s. That, however, was not the real payoff. According to Briody, Brown & Root subsequently worked on 88 different jobs for Texas Eastern, and generated revenues of $1.3 billion from Texas Eastern between 1947 and 1984. [42.1]

According to Robert Sobel in The Life and Times of Dillon Read, under August Belmont’s personal leadership of the transaction, Dillon Read also made a profit on the Texas Eastern shares. “Nothing is known of Dillon Read’s profits on the underwriting, but it was a sizeable owner of TETCO [Texas Eastern] common, acquired at 14 cents a share, which rose to $9.50.” [42.2] While figures for Dillon Read revenues from underwriting and other investment banking services over the years comparable to Brown & Root’s construction contracts are not available, my recollection was that Dillon continued to maintain a profitable relationship with Texas Eastern when I worked at the firm in the 1980s many decades later. Interestingly enough, Briody also describes in detail the McCarthyist efforts that were made to destroy Federal Power Commission chairman Leland Olds, an honest government official, because his ethical regulatory decisions threatened the richness of the Texas Eastern profits. The clear implication is that the pattern of generating financial windfalls from government privatizations combined with dirty tricks against honest government officials is nothing new. [42.3]

The closeness of the Brown & Root relationship with Dillon Read is also underscored by Briody’s description of the head of Brown & Root’s frustration with Lyndon Johnson’s decision to serve as John Kennedy’s running mate. He quotes August Belmont, by then a leader of Dillon Read, who was with Brown in Houston in his private hotel suite listening to the radio coverage of Johnson’s announcement. According to Belmont, “Herman Brown….jumped up from his seat and said, ‘Who told him he could do that?’ and ran out of the room.” [42.4]

What Briody does not mention is allegations regarding Brown & Root’s involvement in narcotics trafficking. Former LAPD narcotics investigator Mike Ruppert once described his break up with fiance Teddy — an agent dealing narcotics and weapons for the CIA while working with Brown & Root, as follows:

“Arriving in New Orleans in early July, 1977 I found her living in an apartment across the river in Gretna. Equipped with scrambler phones, night vision devices and working from sealed communiqués delivered by naval and air force personnel from nearby Belle Chasse Naval Air Station, Teddy was involved in something truly ugly. She was arranging for large quantities of weapons to be loaded onto ships leaving for Iran. At the same time she was working with Mafia associates of New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello to coordinate the movement of service boats that were bringing large quantities of heroin into the city. The boats arrived at Marcello controlled docks, unmolested by even the New Orleans police she introduced me to, along with divers, military men, former Green Berets and CIA personnel.

“The service boats were retrieving the heroin from oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, oil rigs in international waters, oil rigs built and serviced by Brown and Root. The guns that Teddy monitored, apparently Vietnam era surplus AK 47s and M16s, were being loaded onto ships also owned or leased by Brown and Root. And more than once during the eight days I spent in New Orleans I met and ate at restaurants with Brown and Root employees who were boarding those ships and leaving for Iran within days. Once, while leaving a bar and apparently having asked the wrong question, I was shot at in an attempt to scare me off.”[43]

Source: “Halliburton’s Brown and Root is One of the Major Components of the Bush-Cheney Drug Empire” by Michael Ruppert, From the Wilderness

Another important relationship for the Houston-based Cornell Corrections was the California Department of Corrections. Whether this reflected that California was home base for David Cornell’s former employer, Bechtel, is not clear. When Cornell Corrections got started, California had the largest prison population of any U.S. governmental entity. In part due to extraordinary growth in incarcerations of non-violent drug users as a result of the War on Drugs, the federal prison population managed by the Federal Bureau of Prisons at the Department of Justice has become the largest with 186,560 based on their September 8, 2005 weekly update.[44] California is close behind with 168,000 youths and adults incarcerated in California prisons and 116,000 subject to parole.

Cornell’s early years of business were not financially profitable. The private prison industry faced significant resistance and legal and operational challenges to privatizing federal, state and local prison capacity. Within the private prison industry, Cornell faced competition for new contracts and acquisitions from two larger, more experienced companies, CCA and Wackenhut. By 1995, compared to industry leaders, Florida-based Wackenhut and Tennessee based Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), Cornell Corrections appeared to be lagging in government contract growth. As of mid 1996, Cornell was carrying $8 million of cumulative losses on its balance sheet.

Cornell’s Chief Financial Officer, Treasurer and Secretary was Steven W. Logan, who had served as an experienced manager in Arthur Anderson’s Houston office. This was the same office of Arthur Anderson that had served as Enron’s auditor until the Enron bankruptcy brought about the indictment and conviction of Arthur Andersen.[45] Arthur Andersen was Cornell’s auditor, having first served as a consultant to create market studies which helped support the approvals for and financing of the building of the Rhode Island facility for the U.S. Marshals Service. Logan was later forced out of Cornell after an off-balance sheet deal[46]engineered with the help of a former Dillon Read banker Joseph H. Torrence, like those done for Enron was called into question and significant stock value declines triggered litigation from shareholders.

Cornell’s Reported Revenues and Net Income for 1992-1996

Most venture capital investors prefer to exit their investment within 5 years. That means that Dillon Read would have likely wanted to establish or start their exit from Cornell by 1996. The stock market was hungry for Initial Pubic Offerings (IPOs) where a new company sells its stock to the public for the first time. Venture capitalists typically make their profit from financing a company and then selling their equity when a public market has been established for the company’s stock. However, by the end of 1995, Cornell’s story was not an exciting one. It was not a market leader, its growth was slow and it had no profits. If the calf was going to be taken to market, it would need fattening.

A Note on “Prison Pop”

The “pop” is a word I learned on Wall Street to describe the multiple of income at which a stock is valued by the stock market. So if a stock like Cornell Corrections trades at 15 times its income, that means for every $1 million of net income it makes, it’s stock goes up $15 million. The company may make $1 million, but its “pop” is $15 million. Folks make money in the stock market from the stock going up. On Wall Street, it’s all about “pop.”

Prison stocks also are valued on a “per bed” basis — which is based on the number of beds provided and the profit per bed. “Per bed” is really a euphemism for people who are sentenced to be housed in their prison.

For example, in 1996, when Cornell went public, based on the financial information provided in the offering document provided to investors, its stock was valued at $24,241 per bed. This means that for every contract Cornell got to house one prisoner, at that time, their stock went up in value by an average of $24,261. According to prevailing business school philosophy, this is the stock market’s current present value of the future flow of profit flows generated through the management of each prisoner. This, for example, is why longer mandatory sentences are worth so much to private prison stocks. A prisoner in jail for twenty years has a twenty-year cash flow associated with his incarceration, as opposed to one with a shorter sentence or one eligible for an early parole.[47] This means that we have created a significant number of private interests — investment firms, banks, attorneys, auditors, architects, construction firms, real estate developers, bankers, academics, investors among them— who have a vested interest in increasing the prison population and keeping people behind bars as long as possible.

When you invest in stock, you make money if and when you sell the stock at a higher price than you paid for it. This would be true for the people who invested in Cornell stock, including Dillon Read and its venture funds. Cornell was run by a board of directors that represented the shareholders, particularly the controlling shareholders — in this case Dillon Read. The board is the group of people who decides what goes. Senior management officials, such as the founder and Chairman David Cornell, who run the company day to day, are also on the board. Most of the money they make comes from stock options that they get to encourage them to get the stock to go up for the investors. That means that what everyone who runs the company wants is for the stock to go up.

There are two ways to make the stock go up. First, you can increase net income by increasing capacity — the number of “beds” — or profitability — “profits per bed.” Second, you can increase the multiple at which the stock trades by increasing the markets’ expectations of how many beds or what your profit per bed will be and by being very accessible to the widest group of investors. So, for example, passing laws regarding mandatory sentencing or other rules that will increase the needs for prison capacity can increase the value of private prison company stock without those companies getting additional contracts or business. The passage of — or anticipation of — a law that will increase the demand for private prisons is a “stock play” in and of itself.

The winner in the global corporate game is the guy who has the most income running through the highest multiple stocks. He is the winning “pop player.” Like the guy who wins at monopoly because he buys up all the properties on the board, he can buy up the other companies. So the private prison company that wins is the one that gets the most contracts that guarantee it the most prisons and prisoners that generate the most income for the longest period with the smallest amount of risk.

The way that Cornell could become a winner quickly was to get lots of government contracts to house lots of prisoners and acquire other companies with government contracts to house lots of prisoners and do it quickly.[48] And that was exactly what happened.

X. The Clinton Administration: Progressives for For-Profit Prisons

Much has been written about the use of the War on Drugs to intentionally disenfranchise poor people and engineer the centralization of political and economic power in the U.S. and globally, including an explosive rise in the U.S. prison population. The purpose of this story is not to repeat this fundamentally sound thesis. For those who are interested in more on this topic, I would refer you to my article and audio seminar “Narco Dollars for Beginners” as well as Michael Woodiwiss’ book Organized Crime and American Power (University of Toronto Press, 2001) and their associated bibliographies.[49]

What most people miss is the extent to which the day-to-day implementation of this intentional centralism is deeply pervasive and therefore deeply bipartisan. It receives the promotion and support from all political and social spectrums that make money by running government through the contractors, banks, law firms, think tanks and universities that really run the government. My intention for this story is to make clear how the system really works. A system in which a small group of ambitious insiders — who more often than not were educated at Harvard, Yale, Princeton and the other Ivy League schools — enjoy centralizing power and advantaging themselves. Paradigms of Republican vs. Democrat or Conservative vs. Progressive have been designed for obfuscation and entertainment. An endless number of philosophies and strains of religious and “holier than thou” moralism are really put on and taken off like fresh make-up in the effort to hide from view a deeper, uglier face. One person who may have described it more frankly during the Clinton years was the former Director of the CIA, William Colby, who writing for an investment newsletter in 1995 said:

“The Latin American drug cartels have stretched their tentacles much deeper into our lives than most people believe. It’s possible they are calling the shots at all levels of government.”

The Clinton Administration took the groundwork laid by Nixon, Reagan and Bush and embraced and blossomed the expansion and promotion of federal support for police, enforcement and the War on Drugs with a passion that was hard to understand unless and until you realized that the American financial system was deeply dependent on attracting an estimated $500 billion-$1 trillion of annual money laundering. Globalizing corporations and deepening deficits and housing bubbles required attracting vast amounts of capital.

Attracting capital also required making the world safe for the reinvestment of the profits of organized crime and the war machine. Without growing organized crime and military activities through government budgets and contracts, the economy would stop centralizing. The Clinton Administration was to govern a doubling of the federal prison population.[50]

Whether through subsidy, credit and asset forfeiture kickbacks to state and local government or increased laws, regulations and federal sentencing and imprisonment, the supremacy of the federal enforcement infrastructure and the industry it feeds was to be a Clinton legacy.

One of the first major initiatives by President Bill Clinton was the Omnibus Crime Bill, signed into law in September 1994. This legislation implemented mandatory sentencing, authorized $10.5 billion to fund prison construction that mandatory sentencing would help require, loosened the rules on allowing federal asset forfeiture teams to keep and spend the money their operations made from seizing assets, and provided federal monies for local police. The legislation also provided a variety of pork for a Clinton Administration vogue constituency — Community Development Corporations (CDCs) and Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). The CDCs and CDFIs became instrumental during this period in putting a socially acceptable face on increasing central control of local finance and shutting off equity capital to small business.

The potential impact on the private prison industry was significant. With the bill only through the house, former Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti joined the board of Wackenhut Corrections, which went public in July 1994 with an initial public offering of 2.2 million shares. By the end of 1998, Wackenhut’s stock market value had increased almost ten times. When I visited their website at that time it offered a feature that flashed the number of beds they owned and managed. The number increased as I was watching it — the prison business was growing that fast.

However, the Clinton Administration did not wait for the Omnibus Crime Bill to build the federal enforcement infrastructure. Government-wide, agencies were encouraged to cash in on support in both Executive Branch and Congress for authorizations and programs — many justified under the umbrella of the War on Drugs — that allowed agency personnel to carry weapons, make arrests and generate revenues from money makers such as civil money penalties and asset forfeitures and seizures. Indeed, federal enforcement was moving towards a model that some would call “for profit” faster than one could say “Sheriff of Nottingham.”

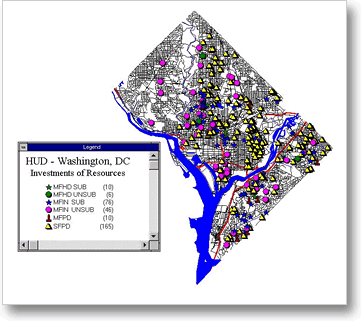

On February 4, 1994, U.S. Vice President Al Gore announced Operation Safe Home, a new enforcement program at HUD. Gore was a former Senator from Tennessee. His hometown of Nashville was home of the largest private prison company, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). He was joined at the press conference by Secretary of the Treasury Lloyd Bentsen, Attorney General Janet Reno, Director of Drug Policy Lee Brown and Secretary of HUD Henry Cisneros who said that the Operation Safe Home initiative would claim $800 million of HUD’s resources. Operation Safe Home was to receive significant support from the Senate and House appropriations committees. It turned the HUD Inspector General’s office from an auditor of program areas to a developer of programs competing for funding with the offices they were supposed to be auditing — a serious conflict of interest and built-in failure of government internal controls.

According to the announcement, Operation Safe Home was expected to “combat violent crime in public and assisted housing.” As part of this program, the HUD Office of Inspector General (OIG) coordinated with various federal, state and local enforcement task forces. Federal agencies that partnered with HUD included the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Secret Service, the U.S. Marshal’s Service, the Postal Inspection Service, the U.S. Customs Service, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ). The primary performance measures reported in the HUD OIG Semi-Annual Performance Report to Congress for this program are the total number of asset forfeitures/seizures, equity skimming collections and arrests. Subsequent intra-agency efforts such as the “ACE” program sponsored by DOJ and initiated by U.S. Attorney’s Offices, working with the DOJ Asset Forfeiture Fund, HUD OIG and HUD Office of General Counsel promoted revenue generating activities as well.

Behind the scenes what all this meant was big budget increases for DOJ and the portions of the agencies that were focused on profitable enforcement and the War on Drugs. Big budget increases meant big contract budget increases as government outsourced more and more work. In “Prisons for Profit: A special report; Jail Business Shows Its Weaknesses,” Jeff Gerth and Stephen Labaton in the New York Times in November 1995 describe the political appointees in the Clinton Administration who were successful at overcoming the natural intelligence of the career civil service at DOJ:

“In the middle of last year, the White House sent its proposal to privatize prisons to the Justice Department, where it was greeted with a frosty response, according to officials involved in the discussions.

To help overcome the resistance of senior officials at the Justice Department and the Bureau of Prisons, the plan’s architect at the White House, Christopher Edley Jr., asked Mr. Gore’s office to turn up the heat.

Mr. Edley, an associate director of the Office of Management and Budget, enlisted the aid of Ms. Kamarck, Mr. Gore’s senior policy adviser overseeing his government review. She then called her friend, Ms. Gorelick, the Deputy Attorney General, who oversees the day-to-day operations of the Justice Department.

I convinced Jamie to do more of it,” Ms. Kamarck recalled.

Cornell Corrections was one of the beneficiaries of Chris Edley, Elaine Kamarck and Jamie Gorelick’s efforts. According to Cornell’s 1996 Prospectus (the offering document provided to investors) filed with the SEC, after building a capacity of approximately 1100 beds over a five year period, Cornell in a nine month period was suddenly blessed with a feeding frenzy of new contracts, contract renewals and contract acquisition approvals that nearly tripled their capacity — all from the Federal Bureau of Prisons at the Department of Justice.

Contract Awards, Renewals and Acquisition Approvals to Cornell Corrections by DOJ, September 1995 to April 1996

The acquisition of the Big Spring, Texas facilities from MidTex, signed in February of 1996 and closed in July 1996 brought on board Charles J. Haugh to be Cornell’s Director of Secure Institutions as of May 1997. Haugh had most recently been the Executive Director of MidTex. From 1963 to 1988, Haugh had served in numerous capacities for the Federal Bureau of Prisons at DOJ, including Special Assistant to Director Administrator of Correctional Services Branch, Associate Warden, Chief Correctional Supervisor and Correctional Officer.

Gerth and Labaton in “Prisons for Profit” describe who in the Clinton Administration got it done:

“Federal officials say they are comfortable with letting private companies run Federal prisons because the industry has become mature, gaining experience running state and local jails. But Federal officials have also grown comfortable with the prison industry because its ranks now include many former colleagues as senior and other law-enforcement officials have taken positions at private corrections companies, Washington’s latest revolving door profession.

The industry leader is the Corrections Corporation of America, a 12-year-old company based in Nashville. Some of the company’s officials are former Federal prison employees, and the company’s director of strategic planning, Michael Quinlan, headed the Bureau of Prisons in the Bush Administration.

Another industry leader is the Wackenhut Corrections Corporation of Coral Gables, Florida. Its directors include Norman A. Carlson, Mr. Quinlan’s predecessor as the director of the prisons bureau, and Benjamin R. Civiletti, a former Attorney General.

The Acting Attorney General in the first months of the Clinton Administration, Stuart Gerson, is on the board of Esmor Correctional Services of Sarasota, Fla. Four months ago, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, a unit of the Justice Department, canceled its contract with Esmor after an uprising at its detention center in Elizabeth, N.J. An investigation by immigration officials concluded that Esmor, trying to cut costs, had failed to train guards, some of whom beat detainees.

The revolving door is beginning to work both ways. Not only has the private sector turned to former Federal officials, the Government has also started to look to industry leaders for aid in developing plans to hand new prisons over to private management.

Mr. Crane, a general counsel at the Corrections Corporation in the 1980s, was retained briefly as a consultant by the Bureau of Prisons to help write a model contract that is going to be used to hire the company to run the Federal prison in Taft.

The Mr. Crane who they have hired to develop the contract is the same Mr. Crane who arranged for the prisoners to be shipped from North Carolina to Rhode Island to save Cornell Corrections and Dillon Read’s municipal bond buyers.

The outpouring of contracts from the Department of Justice to Cornell was very significant. When Cornell did its IPO in October of 1996, I estimate it had an implied “per bed” or “per prisoner” valuation of $24,241. Valuing the company at the IPO price, the total company value was $81 million. Without the contracts from the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the company value would have been approximately $39 million, assuming the company could have held a $24,241 per prisoner multiple or come to market at all — both unlikely in my opinion. The increase in total valuation of stock held by Dillon and its funds based on these assumptions would have been a minimum of $18.5 million. In short, the Dillon Read officers and directors invested in Cornell experienced a more than double in the increase in their value of their personal holdings of Cornell stock as a result of six months of contract decisions by DOJ and its agencies.

Deputy Attorney General Jamie Gorelick, who according to the New York Times article had overseen the new policy of prison privatization, left DOJ in 1997. She then became a Vice Chair of Fannie Mae, a “government sponsored enterprise.” This means it is a private company that enjoys significant governmental support. Fannie Mae buys mortgages and combines them in pools. They then sell securities in these pools as a way of increasing the flow of capital to the mortgage markets.

The reader can appreciate why Wall Street would welcome someone as accommodating as Gorelick at Fannie Mae. This was a period when the profits rolled in from engineering the most spectacular growth in mortgage debt in U.S. history.[51] As one real estate broker said, “They have turned our homes into ATM machines.” Fannie Mae has been a leading player in centralizing control of the mortgage markets into Washington D.C. and Wall Street. And that means as people were rounded up and shipped to prison as part of Operation Safe Home, Fannie was right behind to finance the gentrification of neighborhoods. And that is before we ask questions about the extent to which the estimated annual financial flows of $500 billion–$1 trillion money laundering through the U.S. financial system or money missing from the US government are reinvested into Fannie Mae securities.

It is important before closing this description of Cornell’s extraordinary good fortune with the Federal Bureau of Prisons and DOJ in the fall of 1995 and the spring and summer of 1996 to provide some additional context. During this period, America was in the middle of a Presidential election. Bill Clinton and Al Gore were running for their second term. Dillon Read was a traditionally Republican firm, with the largest Dillon investors in Cornell giving generously to the Republican Party as well as to the Dole-Kemp campaign, whose campaign manager, Scott Reed, had been Kemp’s chief of staff at HUD and then Executive Director of the Republican Party. The corporate ancestry and relations of Cornell — Bechtel, Houston, their auditor, Arthur Anderson’s Houston office, their attorney, Baker Botts, and their construction company, Halliburton/KBR — are ties all deeply associated with the Bush family and Republican camp.

Federal Campaign Donations of Seven Largest Dillon Investors in Cornell Corrections Found in Center for Responsive Politics Database – 1995 & 1996

If you want to see a bi-partisan system at work, follow the money. In the middle of a Presidential election, a Democratic administration engineered significant equity value into a Republican firm’s back pocket. If you step back and take the longer view, however, what you realize is that many of the players involved appear to have connections to Iran Contra and money laundering networks. A surprising number of them went to Harvard and other universities whose endowments are significant players in the investment world. And as it turned out, while the U.S. prison population was soaring from 1 million to 2 million people and US government and consumer debt was skyrocketing, Harvard Endowment was also growing — from $4 billion to $19 billion during the Clinton Administration. Harvard and Harvard graduates seemed to be in the thick of many things profitable.

XI. Hamilton Securities Group

I left the Bush Administration in 1990, persuaded that digital technology and the Internet could be used by entrepreneurs to create new wealth in an investment model that created alignment between global investors and the land, environment and people. If we financed places with equity instead of debt, we could create a way for global investors to profit from reducing consumption of scarce resources, integrating new technology into our infrastructure, healing the environment and improving my rule of thumb for the health of a community — the Popsicle Index.[52] The Popsicle Index is the percentage of people in a place who believe a child can leave their home and go to the nearest place to buy a popsicle or snack and come home alone safely.[53]

When I was a little girl growing up in West Philadelphia, the Popsicle Index was close to 100%. The Dow Jones was 150. Today, in my old neighborhood the Popsicle Index has fallen about 90% to 10% while the Dow Jones has risen more than sixty times to over 10,000. In short, we have a win-lose relationship between investors and communities. In addition, we also have a win-lose relationship between government and communities. For more than fifty years we have had steadily rising government budgets for programs and enforcement (often justified on the theory that they will make the Popsicle Index go up) and a steadily falling Popsicle Index.

In 1991, at the same time that Dillon was bankrolling the Cornell Corrections start-up, I started an investment bank and financial software firm in Washington called The Hamilton Securities Group. Hamilton was named after Alexander Hamilton, one of the key drafters of the U.S. Constitution. While I served as Assistant Secretary of Housing-FHA Commissioner at HUD, I tried on numerous occasions to persuade Secretary of HUD Jack Kemp and his staff not to propose new policies that would result in the abrogation of government contracts or contractual obligations with respect to financial assets. I had a deputy who always reminded me that Alexander Hamilton had gone through a similar process of ensuring that the government did not illegally abrogate its obligations and debts when he was the first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States — and that Hamilton had always prevailed. Numerous Alexander Hamilton quotes became part of our way of cheering ourselves up in the midst of cleaning up nauseating levels of corruption. Sayings like “A promise must never be broken.”

One of The Hamilton Securities Group’s goals was to map out how the flows of money worked in the U.S. and create software tools that would make this information accessible to communities. We believed that the way to re-engineer government was for citizens to have access to the information about the sources and uses of taxes and government spending and financing in their communities, and to participate in the process of making sure that these investments were managed to restore our neighborhoods to a “Popsicle Index” of 100%. Transparency is essential for private markets to work and for government investment to be economically productive, accountable to those who fund it and managed according to the laws that are supposed to govern such investment. Otherwise, we will veer toward subsidizing private interests that are powerful politically or forceful, including through dirty tricks and economic warfare, as opposed to those that are productive.

After I started The Hamilton Securities Group, I was approached by Nick Brady, still Secretary of Treasury, to serve as a Governor of the Federal Reserve. When I declined, John Sununu, then White House Chief of Staff, had me appointed to the board of Sallie Mae, the corporation that helps to provide financing for student loans. While on the board of Sallie Mae, I was taken aside by the Chairman who explained that it was essential for me to ask Nick to sponsor me for membership in the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). When I said that this was not something I felt comfortable doing, he said, quite alarmed in a generous and caring manner, “You don’t understand, if you don’t join the Council, you will be out for good.”

I did not join the CFR and in retrospect — after years of watching how the CFR and its members operate — believe I made a sound decision. My dream was to find solutions. That required getting in the trenches to prototype money maps, tools and transactions. Prototyping of this type requires high degrees of trust with diverse networks — in communities and financial markets alike. Some of these networks would not welcome a central banker or members of organizations like the CFR that provide the intellectual smokescreen for the centralization of financial data and flows and economic and political power.

Over time I was increasingly shocked by the speed and ease with which many intelligent and seemingly competent members of the CFR appeared to eagerly justify policies and actions that supported growing corruption. The regularity with which many CFR members would protect insiders from accountability regarding another appalling fraud surprised even me. Many of them seemed delighted with the advantages of being an insider while being entirely indifferent to the extraordinary cost to all citizens of having our lives, health and resources drained to increase insider wealth in a manner that violated the most basic principles of fiduciary obligation and respect for the law. In short, the CFR was operating in a win-lose economic paradigm that centralized economic and political power. I was trying to find a way for us to shift to a win-win economic paradigm that was — by its nature — decentralizing.

The Hamilton Securities Group was financed with the money I made as a partner of Dillon Read and the sale of my home in Washington and then financed internally with reinvested profits from operations. Several years after starting, we won a contract by competitive bid to serve as the lead financial advisor to the Federal Housing Administration FHA at HUD. As a result, I had the opportunity to serve the Clinton Administration in the capacity of President of The Hamilton Securities Group in addition to having served as Assistant Secretary of Housing-FHA Commissioner in the first Bush Administration.[54]

One of our assignments for HUD was serving as lead financial advisor for $10 billion of mortgage loan sale auctions. Using online design books[55] and our own analytic software tools as well as bidding technology from Bell Laboratories we adapted for financial applications, we were able to significantly increase HUD’s recovery performance on defaulted mortgages, generating $2.2 billion of savings for the FHA Mutual Mortgage Insurance and General Insurance Funds.

While we plowed all of our profits back into the expenses of building databases and software tools and into banking a community-based data servicing company, we were still profitable, generating $16 million of fee revenues and $2.3 million of net income in 1995.[56]

While the loan sales were a great success for taxpayers, homeowners and communities, it turned out that they were a significant threat to the traditional interests that fed at the trough of HUD programs, contracts and related FHA mortgage and Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgage securities operations.

For example, if you illuminated the sources and uses of government resources on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis, you would see that government monies were spent in ways that created fat stock market and personal profits for insiders at the expense of more productive outsiders who are providing most of the tax and other resources used. Insiders could include big developers and property management companies that specialized in HUD-subsidized properties like then Harvard Endowment-owned National Housing Partners (NHP) and their affiliated mortgage banking operations like NHP’s Washington Mortgage (WMF), or for investment bankers like Dillon Read or Stephens, Inc. who issued municipal housing bonds for agencies like the Arkansas Development and Finance Agency (See “Narco Dollars in the 1980s—Mena Arkansas” above). When I suggested to the head of HUD’s Hope VI public housing construction program during the Clinton Administration that she could spend $50,000 per home to rehab single family homes owned by FHA rather than spending $250,000 to create one new public housing apartment in the same community, she got frustrated and said “How would we generate fees for our friends?”

Our efforts at The Hamilton Securities Group to help HUD achieve maximum return on the sale of its defaulted mortgage assets coincided with a widespread process of “privatization” in which assets were, in fact, being transferred out of governments worldwide at significantly below market value in a manner providing extraordinary windfall profits, capital gains and financial equity to private corporations and investors. In addition, government functions were being outsourced at prices way above what should have been market price or government costs — again stripping governmental and community resources in a manner that subsidized private interests. The financial equity gained by private interests was often the result of financial, human, environmental and living equity stripped and stolen from communities — often without communities being able to understand what had happened or to clearly identify their loss. This is why I now refer to privatization as “piratization.”

One of the consequences was to steadily increase the political power of companies and investors who were increasingly dependent on lucrative back door subsidies — thus lowering overall social and economic productivity. Hence, the doubling of FHA’s mortgage recovery rates from 35% to 70-90% ran counter to global trends and ruffled feathers. FHA, with Hamilton’s help, was requiring investors like Harvard Endowment to pay full price for assets while it appeared that they and investors like them were engineering progressively deeper and deeper windfall discount prices as part of government privatization programs elsewhere in the U.S. and globally. A Federal False Claims Act lawsuit against Harvard and journalist coverage regarding their role as a USAID government contractor in Russia illuminated the extent of the windfall profits that they and members of their networks were able to engineer at the expense of the Russian people, investors and the American people.[57]A criticism that I now have that I did not understand at the time was that even efficiently and honestly executed privatization transactions such as the HUD loan sales policies which insist on open competition at the highest price run the risk of advantaging players who were the most successful at laundering money for the “black budget.” All solutions to this problem bring us back to the importance of place-based transparency of government resources and the importance of investing in the equity of small businesses and small farms.

Things took an even darker turn when we started Edgewood Technology Services, a data servicing company in a largely African-American residential community in Washington, D.C.[58] Our investment in Edgewood gave us the ability to develop a skilled dedicated workforce that could help us build much more powerful databases and software tools. It also helped us understand the investment opportunity to train people working at minimum wage jobs or living on subsidies to develop more marketable skills and earning power by doing financial data servicing and software development.

From the financial information that emerged from our portfolio strategy work for HUD and from our investment in Edgewood, we discovered that it was less expensive to train people to do these jobs than to fund their living on government subsidies indefinitely, let alone going to prison. For example, a woman with two children living in subsidized housing in Washington, D.C. on welfare and food stamps cost the government $35-55,000 or more. In 1996, the General Accounting Office (GAO) published a study showing that on average total annual expenditures for federal, state and local prisoners was over $150,000 per prisoner. Presumably this included all overhead and capital costs but did not include the costs of supporting minor children of such prisoners. If government funded the care of her two children while she was in prison, those costs would be in addition.

What we found at Edgewood was that there was a portion of the work force that, due to obligations to children and elderly parents, was not able to commute. Some of these people could be a productive work force working near their home and developing computer and software skills at their own pace. If training was combined with the creation of jobs, the economics of training people to do these jobs were sustainable and with proper screening and management could be profitable for the private sector. The potential savings to the public sector was astonishing — not to mention the potential improvement in quality of life for cities, suburbs and rural communities. With government leadership and large corporations actively working to move jobs abroad, people in all areas of the U.S. would need these kinds of new skills and jobs. Moreover, small businesses would need access to the kinds of venture capital and financial equity we were proposing to invest in community venture capital. That meant that communities needed to circulate more deposits and savings internally rather than depositing and investing their funds in large banks and corporations that used those funds to win local market share away from small businesses and farms.

During this period, The Hamilton Securities Group helped HUD develop a program to permit owners of HUD-subsidized projects to treat some of the costs of community learning centers as “allowable costs” that could be funded from property cash flows. This allowed apartment building operations in communities experiencing welfare reform, cutbacks in domestic programs and unemployment from jobs moving abroad to provide facilities and programs that could help residents improve their ability to generate income. It encouraged linkages between private real estate managers and community colleges and other organizations committed to helping people learn new skills.

As I traveled and researched around the country, it became apparent that data servicing jobs like those we were prototyping at Edgewood were highly competitive with jobs in the illegal economy. In other words, data servicing jobs paying $8-10 per hour and offering health care benefits and the opportunity to improve skills had the potential to attract a surprising number of people away from dealing drugs, prostitution and other street crime. The Hamilton Securities Group’s primary competition for the younger multi-racial portion of this work force appeared to be organized crime and the industries dependent on the continuation of organized crime activities — including enforcement and private prisons.

Meanwhile, The Hamilton Securities Group’s growing software and database infrastructure about public and private resource flows in communities indicated that the vast majority of government subsidies were either not necessary or not economic — whether welfare and HUD subsidies or prisons and the huge and growing infrastructure of community and social development and private real estate and government contractors that they supported. There was a much more economic way for government to reduce domestic subsidies and crime. Billions of dollars of government investment had a negative return on investment. We were paying millions of people — whether on welfare or government contracts or HUD property subsidies — to do things that were not productive. Change those expenditures to a positive return on investment, and extraordinary improvements in productivity were possible. There was much work needed to be done that warranted investment — from repairing our infrastructure to rebuilding communities. As part of the potential opportunities, with both the private sector and federal government predicting very significant increases in the need for data servicing support and other jobs that could be outsourced through telecommunications, there appeared to be a significant opportunity. We shared our data and results with HUD, The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Congress and the Office of Management and Budget at the White House, and with leaders within the real estate and community development industries.

The initial response was very positive from a number of quarters, particularly those people most concerned with the growing federal debt and issues of productivity. I will never forget one of our meetings with a senior White House official. We showed him our initial estimates of the savings that were possible from potential reduced subsidy expenditures as well as lower default rates on federal mortgage and loan programs as a result of increased employment and income in low and moderate communities. He was ecstatic about the potential to save billions while reducing poverty — all recently made possible by new technology. He and many other government officials — when they saw the initial estimates emerging from the loan sales and our aggregates of the extraordinary amounts of federal monies being wasted by place — realized the potential when a negative financial return on investment is reengineered to a positive return on investment in a place.

Private investment leaders were also enthusiastic. During one presentation, the head of portfolio strategy for one large corporate fund said with astonishment, “This is terrific. We can save the country and make a fortune doing it.” Making a fortune was a good thing. One of our biggest concerns was achieving a sufficient investment performance on pension fund capital to ensure that retirement benefits were adequately funded. Hamilton was proposing a financial model that would also help fund retirement obligations as a result of pension funds profiting from the wealth created by reducing poverty.

Others were not so positive, including special interests whose business had become managing “the poor” and who would be out of a business if new tools and opportunities were to significantly decrease the number of people who were poor. Many of these were traditionally powerful Democratic constituencies, including private for-profits, foundations, universities and not-for-profit agencies that had built up a significant infrastructure servicing and supporting programs to house, feed and supervise poor people. If people were no longer poor, what was their purpose? When we made a presentation to a group of leading foundations, in partnership with a Los Angeles entertainment company interested in using entertainment skills to make training fun, the head of low-income programs at Fannie Mae told me that it was the most depressing presentation he had ever seen. It implied that the poor did not need his help — that his life and work had no meaning. It appeared he did not want to end poverty. His personal meaning was derived from poverty continuing, if not growing. Real estate interests that were hoping to gentrify neighborhoods as a result of welfare reform were also not pleased. They would make more money turning over populations rather than helping the current population improve without moving. Their allies were enforcement teams like the HUD OIG that won funding and generated revenues from helping to get one group out, so another group could be moved in.

We were warned that the HUD Inspector General’s office had a very negative response to the “neighborhood networks” model of community learning centers, with one of the enforcement team members referring to such efforts as “computers for niggers.” Essentially, the vision we were proposing was in competition with their enforcement business, which consisted of dropping 200 person “swat” teams into a neighborhood to round up and arrest lots of young people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time and could not afford an attorney. This required a fundamentally different approach and philosophy. One model proposed helping the people in a place improve. The other proposed rounding them up and pushing them out so that new people could be moved in.

The highly successful HUD loan sales had also run into a problem with the staff of the HUD Inspector General’s Office. According to HUD staff, the HUD OIG staff wanted the HUD loan sale staff to withdraw loans from sale portfolios so they could pursue civil money penalties against the building owners. If the loans were sold, it would be better for the FHA fund and for building residents and the surrounding communities. However, it would make less money for the “Sheriff of Nottingham” business in HUD OIG. The IG and General Counsel staff were apparently indifferent to overall best interests of the government on a government wide basis let alone taxpayers and communities.

Years later, when HUD Inspector General Susan Gaffney was asked during a deposition what the recovery rates were on HUD’s defaulted mortgage portfolio before, during and after the loan sale program that The Hamilton Securities Group pioneered, she said she had no idea. Her attitude suggested that this was not an important piece of information. Which suggests that she found something that had billions of dollars of impact on the FHA Funds each year to be of no interest. The focus in federal enforcement was on activities that made money and garnered funding support and headlines directly for the enforcement teams. This “for-profit ” philosophy was surprisingly blatant. I was reminded of the Congressman who jumped up from dinner to cast his vote in appropriations committee and as he rushed off said to me, “Let’s face it, honey, I’m only here to protect my shit.”

In late 1995, The Hamilton Securities Group began work on Community Wizard, a software tool designed to facilitate community Internet access to all public data and some private data on local resource use, including federal tax, expenditures and credit data. The initial response to the tool from Congress, HUD and our technology networks was astonishing. People were ecstatic to realize that they did not have to continue to live and work in the dark financially. It was a relatively easy thing for new software tools to help people learn about the flow of money and resources in their community. Additional software tool development also resulted in numerous tools to analyze subsidized housing in a place-based context, including detailed pricing tools that combined significant databases on government rules and regulations with all of our pricing data from the various loan sales, with databases about mortgage, municipal and stock market financing of homebuilding and home ownership. Such tools would allow people to take a positive and proactive role in insuring that government resources were well used. Such tools would allow investors to improve the performance of local investment — particularly venture and equity investment in small businesses and farms.

There was only one problem. If communities had easy access to this data, the pro-centralization team of Washington and Wall Street would be in trouble. Everything from HUD real estate companies to private prisons would be shown to make no economic sense — other than to generate private profits and capital gains for insiders. And billions of government contracts, subsidies and financing would be shown to make no economic sense — other than to generate private profits and capital gains for insiders. Indeed, communities were better off without many of these activities and funding. Through our software, private citizens would see the cost of decades of accumulated “fees for our friends.”

A case in point was a meeting I had with a former partner of Dillon Read who I had hoped to recruit to Hamilton in 1996. He came to our offices and during my presentation of our plans for community venture, told me that the situation was hopeless and that our tools would make no difference. I powered up Community Wizard and our software tools on the monitors and asked him where he lived. He said “Bronxville, New York.” I had one of my team print out from our databases a list of federal expenditures in his neighborhood. When he saw the first item, he exploded with rage, “$4 million last year for flood insurance? That is ridiculous. That is corrupt!” $4 million of flood insurance sounded pretty innocent to me and I said, “why is that corrupt?” He said, “Bronxville is on a hill. I have lived in Bronxville for many years and I have never seen or heard of a flood.” It is typical that someone with years of experience in a place can spot potential waste and reengineering opportunities much faster when presented with detailed government financial information than someone who does not know the place.

As the former Dillon Read partner started to read through the details of the annual expenditures, he became more and more upset. The next day we were scheduled to speak by conference call after he returned to New York. I called and called at the appointed time but the line was busy. When I finally got through, he said he had been on the line with the Deputy Mayor of Bronxville for hours going through the data we had provided him. He said, “All this corruption is going to stop.” I said, “I thought you said it was hopeless.” And then he said something to the effect of “that was until I got the numbers for my neighborhood.” He understood that the corruption is funded one neighborhood at a time. If each neighborhood cuts off or reengineers the flow of wasteful or corrupt government funds, the situation can transform in a significant way nationally and globally. You have to cut off the money to the bad guys at the root. And he had realized how much money per person was being wasted when he saw the waste on a human scale where he could both see how the resources could be properly used and could do something about it.

This was, however, before we even addressed the question: “Who was bringing in narcotics and where was all the money from the trafficking and other illegal activities going?” If enough people stopped dealing drugs and taking drugs, then who needed more prisons and all these enforcement agencies and War on Drugs contractors? And how did all of this connect with the stock market and the mortgage markets and the fraud in those markets?

Ask and answer those questions — as communities would now be able to start to do with tools like Community Wizard and our tools — and much Iran-Contra style narcotics trafficking, the private prison industry and the “Sheriff of Nottingham-style” enforcement programs so in vogue at the White House, DOJ and HUD OIG might just be dead in the water. Unfortunately, that might have profound implications for the existing financial market as many corporate and government securities depended on the continued flow of wasted government expenditures.

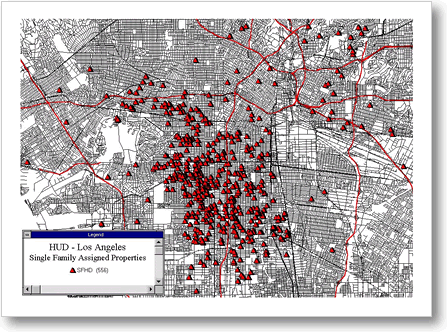

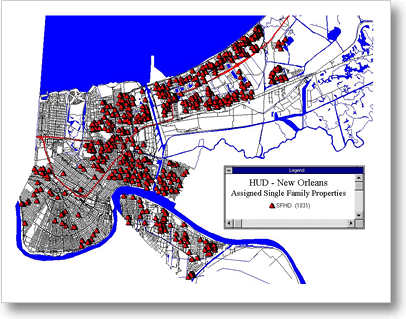

As part of our efforts, we started to publish maps on the Internet of defaulted HUD mortgages in places with significant defaulted mortgage portfolios and to encourage HUD to offer place-based sales that would allow bidders to bid on different types of HUD-related mortgages and properties in one place. If successful, it would permit us to also create bids that optimized total government performance in a particular place — including assets from other agencies as well as contracts, subsidies and services.

One of the maps we put up in the spring of 1996 showed the properties which were financed with defaulted HUD single-family mortgages in South Central Los Angeles, California. The map showed significant HUD defaults and losses in the same area as the crack cocaine epidemic described by Gary Webb in Dark Alliance. Such heavy mortgage default patterns are symptoms of a systemic and very expensive problem — including systemic fraud. This could occur, for example, in situations such as those in which mortgages were being used to finance homes above market prices with inflated appraisals (one of the patterns of HUD fraud documented by the The Sopranos TV show) or where defaulted mortgages or foreclosed properties were being passed back to private parties at below market values, or where these types of mortgage fraud were supporting mortgage securities (such as those issued by Ginnie Mae, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae) that did not have real collateral behind them. This is the type of mortgage fraud that launders profits in a way that can multiply them by many times. Los Angeles was also the area with the largest flow of activities in the Department of Justice’s Asset Forfeiture Fund. Whether drug arrests and incarcerations, legal support for HUD foreclosures and enforcement or asset seizures and forfeitures — these maps were illuminating areas that were big business for “Sheriff of Nottingham-style” operations.

XII. A Note on Protecting the Brand with Dirty Tricks

The process and technology of compromising and controlling honest business and government leaders and journalists — or destroying them when they can not be controlled — are closely guarded secrets known mostly to those who inhabit the covert world or, such as myself, are privileged to have survived their initiation and real world training program. [59] To understand how the process works and the extraordinary resources invested in such dirty tricks first requires an appreciation of the importance of “brand” to the management of organized crime as it is practiced through Wall Street & Washington.

The Wikipedia online encyclopedia defines “brand” as:

“…the symbolic embodiment of all the information connected with a product or service. A brand typically includes a name, logo and other visual elements such as images or symbols. It also encompasses the set of expectations associated with a product or service which typically arise in the minds of people. Such people include employees of the brand owner, people involved with distribution, sales or supply of the product or service, and ultimately consumers.”

A successful venture capitalist like John Birkelund would tell you that a great brand can make or break a company and its stock market value.

The supremacy of the central banking-warfare investment model that has ruled our planet for the last 500 years depends on being able to combine the high margin profits of organized crime with the low cost of capital and liquidity that comes with governmental authority and popular faith in the rule of law. Our economy depends on insiders having their cake and eating it too and subsidizing a free lunch by stealing from someone else. This works well when the general population shares in some of the subsidy, grows complacent and does not see the “real deal” on how the system works. However, liquidity and governmental authority will erode if the general population becomes aware of how things really work. As this happens, they begin to understand the power of innovative technology and re-engineering of government resources to create greater abundance both for themselves and other people. As this happens, they lose faith in the myth that the current system is fundamentally legitimate. This jeopardizes the financial markets that depend on fraudulent collateral and practices to continue to work. It also jeopardizes the wealth and power of the people who are winning with financial fraud.

In short, transparency blows the game and cannot be allowed. No expense will be spared to insure that the insiders — at the expense of the outsiders — control financial data. As Nicholas Negroponte, founding Chairman of the MIT Media Lab, once said, “In a digital age, data about money is worth more than money.”

As a consequence, extraordinary attention and sums of money are invested in affirming the myth and appearance of legitimacy. This includes creating popular explanations of why the rich and powerful are lawful and ethical and the venal poor, hostile foreigners, crafty mobsters and incompetent and irresponsible middle class bureaucrats are to blame for the success of narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and other forms of organized crime.

If the normal successful retail industry — for example, women’s clothing or cars — has an advertising and marketing budget of — let’s just pick a number of say 10% of revenues —then what do we think that an estimated $500 billion–$1 trillion of annual U.S. money laundering flows will spend to protect its market franchise? Working with our number of 10%, how do we think $50-100 billion would be spent to protect the brand — particularly when governmental budgets can be used to fund the effort?

As a result, extraordinary amounts of money and time are spent destroying the credibility of those who illuminate what is really going on. All of this despite the obviousness of the economic reality that those whose wealth is growing the most must have an economic relationship to the business generating the most profit. Or, as in the words of John Gotti, Jr., in response to allegations that the Gotti crime family was dealing drugs, “Who can compete with the government?”

Only when you understand the value of the brand can you understand the extraordinary investment and criminal methods used to stop and suppress our software product Community Wizard and try to frame The Hamilton Securities Group and myself.

XIII. “You are Going to Prison” — 1996

Though a fictional movie, Enemy of the State with Will Smith and Gene Hackman shows how targeting a person works in Washington, D.C. Will Smith plays a Washington lawyer who is targeted in a phony frame-and-smear campaign by U.S. intelligence agency personnel who are afraid that he has evidence of their assassination of a Congressman. The spook types have high-speed access to every last piece of data on the information highway — from Will’s bank account, to his telephone conversations, to his exact location — and the wherewithal to destroy his career and threaten his life.

The organizer of an investment conference once introduced me by saying, “Who here has seen the movie Enemy of the State? The woman I am about to introduce to you played Will Smith’s role in real life.”

One day I was a wealthy entrepreneur with a beautiful home, a successful business and money in the bank. The next day I was hunted, business assets seized, living through some eighteen audits and investigations, a smear campaign directed not just at me but also members of my family, colleagues and friends who helped me, and nine years of highly personalized litigation against The Hamilton Securities Group. For many years, I and those helping me lived with serious physical harassment and surveillance at the hands of mostly unseen, dark forces. Events such as home break-ins, stalking, poisonings, having houseguests followed, friends, colleagues and family warned to not associate with me, a dead animal left on the doormat, and worse became commonplace.[59]

The problems started at the end of 1995 and relentlessly evolved into significant investigation and litigation in 1996.[60] Both frontal and covert attacks came in waves that made no sense to me until we started to map out in chronological form the parallel efforts to suppress Gary Webb’s “Dark Alliance” story, and the timing of stock market profit taking by investors in HUD property managers and private prison companies such as Cornell Corrections. There was a war going on for the rich corporate cash flows determined by the federal budget — between those who made money on building up of communities and a peace economy, and those who made money on the failure of communities and a war economy. As stock market prices and the Dow Jones Index rose, this economic warfare grew in fierceness. For example, a comparison of how DOJ handled The Hamilton Securities Group — a firm that helped communities succeed — versus how it dealt with Enron — a company that criminally destroyed retirement savings and communities — underscores much about the system’s true intentions.[61]

In March 1995, the first billion-dollar HUD loan sale was a significant success. The performance stunned both traditional HUD constituencies and Wall Street. Barron’s published an article, “Believe It or Not, HUD Does Something Right for Taxpayers” (Jim McTague, April 10, 1995). Many were caught off guard by the success of the sale, including the prices that resulted from the combined ingenuity of the investment banking and software technology involved. It established the team at FHA, with The Hamilton Securities Group as lead financial advisor, as significant leaders in authentic reengineering, as opposed to what sounded to me like the press release reengineering coming from Al Gore and Elaine Kamarck’s Office of Reinventing Government.

A hint of the trouble to come was the response from Mike Eisenson, head of the Harvard Endowment’s private equity portfolio. Mike, later to become known for his role in financing George W. Bush’s oil company, Harken Energy, was responsible for Harvard’s investment along with Harvard board member DynCorp Chairman Pug Winokur in National Housing Partnerships (NHP), one of the largest HUD property management companies. As we were preparing to bid the first billion dollar loan sales, Mike picked up his phone when I called him and said to me “Fuck you!” He then proceeded to explain that he hated our bidding process — the only way Harvard could win was by paying more money than the other bidders. One of the reasons that this was a problem was that NHP would be forced to compete for its defaulted mortgages and would be held to market standards on property management fees or would lose management business on properties where HUD transferring the mortgage gave the new owner the right to transfer the property management. NHP was said to be Mike’s single biggest investment. To sell it at a profit, he needed to do NHP to do an IPO. That meant NHP needed more government insider deals, not less.

The bid process I had created was pitting large and small real estate, mortgage and securities investors against each other in a manner that significantly increased competition relative to traditional bidding practices. This resulted in HUD attracting significant new investment interest in buying their defaulted mortgages and significantly higher recoveries on those mortgages. As a result, in approximately $10 billion of loan sales lead by The Hamilton Securities Group, HUD was able to generate $2.2 billion in savings to the FHA Fund. Later audits confirmed that the loan sales had a positive impact for communities in which the properties were located.

One of the many ironies of the loan sales was that J. Roderick Heller III, Chairman and CEO of NHP had asked me to start Hamilton to serve as lead investment bank to NHP. When I joined Rod and Mike at the Harvard Club in the early 1990’s to sign the contract, they tried to significantly change the terms of the deal and essentially abrogated Rod’s verbal contract. If we had proceeded to help NHP as originally planned, we would not have served as lead financial advisor to HUD/FHA. If the Harvard private equity group resented us helping the government regulator of the largest investment in their portfolio, they had no one to blame but themselves.

Another indication of the trouble to come was that I started to receive bizarre e-mails from Tino Kamarck, the husband of Elaine Kamarck who ran Gore’s Office of Reinventing Government at the White House. I had met Tino, who was then #2 at the Export Import Bank and later to be Chairman, when he worked on Wall Street but did not know him well. Out of the blue and by e-mail, he expressed extraordinary and inaccurate notions of my lifestyle and personal habits and proposed that he and I have an affair. I suspected at the time that he had ulterior motives. Sex in Washington, D.C. rarely has anything to do with sex — it’s usually about dirty tricks and dirty politics. One of the inspirations for my starting my own firm had been twenty minutes of listening to Jack Kemp, Secretary of HUD while I was Assistant Secretary, order me to lengthen my skirts. This meeting had nothing to do with my skirts. I suspected that it was an unsuccessful attempt by Jack to get me to lose my temper. I was running the FHA money too cleanly. Despite my offer to move elsewhere in the Administration, Jack preferred to force me out in a manner that could be blamed on me.

To give a sense of the interconnectedness of things, one of our problems appeared to be Jonathan Kamarck, who was on staff in the Senate appropriations subcommittee that was such a significant supporter of HUD’s Operation Safe Home and was uncomfortable with the impact of the HUD loan sales on traditional real estate interests. Jonathan told me that he was Tino’s cousin and so presumably was close to both Tino and Elaine Kamarck. By the time the allegations against The Hamilton Securities Group were discredited and Harvard Endowment had reaped large profits cashing out of their HUD related investments, Elaine was working for Harvard and Tino was working for a real estate firm in Boston that had intimate ties with Harvard and had managed to snag a contract with HUD to do some of the work that The Hamilton Securities Group had been doing. Years later I visited with one of Jonathan’s colleagues on the Senate appropriations subcommittee who had been promoted to chief of staff to the subcommittee chair, Senator Kit Bond, who expressed concern that “HUD was being run as a criminal enterprise.” When only months later the subcommittee engineered a large increase in HUD’s appropriations, I was reminded of what Bill Moyers, former White House Press Secretary, had said on the CIA’s alliance with the Mafia, “Once we decide that anything goes, anything can come back to haunt us.”

The politics took a serious turn when someone from the HUD Inspector General’s Office reported that they were in a meeting with Andrew Cuomo, then Assistant Secretary of Community Development at HUD and soon to be Secretary, and the HUD Inspector General Susan Gaffney. Cuomo reported that he was arranging to get rid of The Hamilton Securities Group and me. Cuomo was considered to be very close to Al Gore and his White House office and efforts to “reengineer government.” Within months, it was reported to me by Nic Retsinas, then Assistant Secretary of Housing, that the White House had ordered him not to hire The Hamilton Securities Group on the next round of contracts — an order which he said he ignored. Later, an associate of the Assistant Secretary of Administration, the appointee who oversees the contracting HUD office, reported to me the same White House orders.

Notwithstanding the orders from on high to the contrary , in January and April of 1996 a new HUD/FHA contract and task order were awarded to The Hamilton Securities Group under which HUD was to pay Hamilton a base of $10 million a year for two years to serve as the FHA’s lead financial advisor. Our successes — from profitable HUD/FHA contract awards to analysis generated by software and database innovations that had Alan Greenspan asking for briefings from our analytics team for the Federal Reserve staff—was a surprise to some who had thought our commitment to technology would not make a significant difference in marketplace transactions and bottom line dollars and sense.

This was a period of risk and transition for many. Dillon Read and John Birkelund were recovering from the unexpected failure of the firm’s lead investor, Barings. After helping the Dillon partners buy the firm back from Travelers in 1991, Barings had collapsed as the result of an Asian trading scandal in early 1995. With Dillon as lead investors, Cornell Corrections was losing money. Former Dillon Chairman and Treasury Secretary, Nick Brady, was learning about the difficulties of starting up his own firm, Darby Overseas Investments, Ltd, in Washington, D.C. The Clinton team was wondering what would happen to them if the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1994 elections translated into their being thrown out in the 1996 elections. Mike Eisenson’s compensation was constrained by publicity regarding salaries paid by Harvard Management and only later was he inspired to start his own firm (with — imagine this — a contract from Harvard Management that paid $10 million a year — the same as The Hamilton Securities Group’s HUD contract.) One can only wonder what was going on behind the scenes at the CIA and DOJ after the Memorandum of Understanding was rescinded in August 1995. Presumably, the rescission left the CIA obligated to report all narcotics trafficking to DOJ and required DOJ to see to it that the CIA satisfied such obligations. Hence, any transparency of the kind that Hamilton was creating with its software tools could significantly increase the criminal liabilities of CIA, DOJ and their contractors. When people are afraid or managing rising risk, they are sometimes jealous of a start-up’s success and frustrated by their inability to openly insist that newcomers respect traditional market relationships, let alone illegal, covert lines of authority and cash flows.